Like everyone else, I’ve spent an appalling amount of time this year reading much too much about Donald Trump. But there’s another Donald I became obsessed with this summer: Donald Hall.

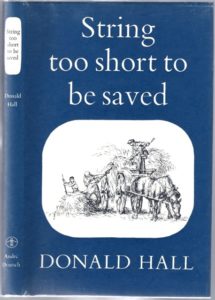

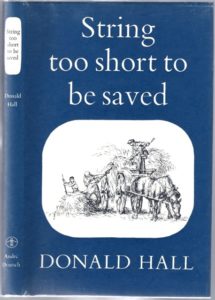

It all started with a magazine story I was writing about Jan and David Hoffman, a pair of furniture makers in rural Pennsylvania who live a life of staggering self-sufficiency. They make their own tools, save their seeds and grow much of their own food. Jan told me they believed in the saying “no string too short to save.” Intrigued by her phrase, I Googled it and found this book:

String Too Short to be Saved is poet Donald Hall’s 1961 memoir of the summers he spent as a youth on his grandparents’ New Hampshire farm in the years leading up to World War II. From the description, it promised to be a sweet, nostalgic beach read that was right up my alley — a string of lyrical anecdotes about tending cows and watching the seasons change. (Basically, a grown-up version of Farmer Boy.) And that alone would have left me plenty satisfied. But the book turned out to be so much more. Hall’s stories about haying, blueberry picking, lost cows and his grandfather’s eccentric farm hand are funny and thrilling enough for kids. I read S & L the chapter called “The Left-Footed Thief,” about the time Donald’s grandfather and his brother hunted down a sheep thief who was wearing two left-footed boots, and they were fascinated.

String Too Short to be Saved is poet Donald Hall’s 1961 memoir of the summers he spent as a youth on his grandparents’ New Hampshire farm in the years leading up to World War II. From the description, it promised to be a sweet, nostalgic beach read that was right up my alley — a string of lyrical anecdotes about tending cows and watching the seasons change. (Basically, a grown-up version of Farmer Boy.) And that alone would have left me plenty satisfied. But the book turned out to be so much more. Hall’s stories about haying, blueberry picking, lost cows and his grandfather’s eccentric farm hand are funny and thrilling enough for kids. I read S & L the chapter called “The Left-Footed Thief,” about the time Donald’s grandfather and his brother hunted down a sheep thief who was wearing two left-footed boots, and they were fascinated.

At the same time, the memoir is also suffused with sadness. From the mysteriously abandoned farm shacks Donald passes on his daily walks with his grandfather to the haunting portraits of long-dead relatives in his grandmother’s hallway there is a pervasive sense of loss in String Too Short. The emotional resonance reminded me of a Donald Hall essay from a couple years ago in The New Yorker in which the former poet laureate showed that at 83, his intellect was still as well-honed and deadly as an axe. Old age, he explained in his growly, godly prose, turned people “invisible.” At one point he described how, at a family dinner, one of his grandchild’s friends placed her chair to sit with her back directly facing Hall, as if his presence was no more than another piece of furniture. I remember his recounting of that moment like a stab in the chest.

String too Short is not by any means intended for kids, but if your 7th or 8th grader doesn’t mind a leisurely read and loved the Little House books and Roald Dahl’s Boy, try it on them.

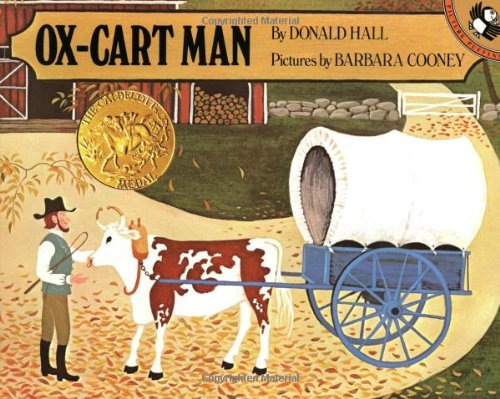

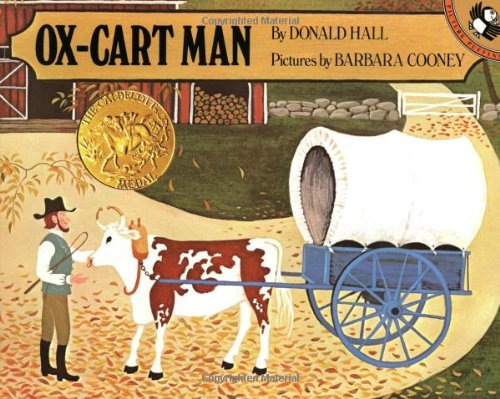

I was so taken with Hall’s tales of frugal farm life I also got this out of the library:

Ox-Cart Man is Hall’s 1979 Caldecott-winning children’s book about a 19th century farmer bringing the goods from his family’s farm to market. It’s one of those slow, bucolic, nothing-really-happens picture books that can be either deadly dull, or, when done right, utterly mesmerizing.

The rhythm of the prose echoes the reassuring rhythm of the farmer’s routines. The farmer packs his ox-cart with brooms, apples and maple syrup; he sells everything (including the ox and the cart) at Portsmouth Market; he buys a needle, a knife, and some peppermint candy for his family; he journeys back home; he and his family start the cycle again. Revisiting the book in light of Hall’s memoir, it’s even more satisfying.

Ox-Cart Man, illustrated by Barbara Cooney

Bonus: With any luck your children will subconsciously absorb the message that in the good old days, kids did their share of labor and were happy if they got a single piece of wintergreen peppermint candy as a treat.

Hall has told interviewers that the surprise success of this book allowed him to put in a new bathroom in the New Hampshire farmhouse he’s lived in since 1975 (it’s the same house where his grandparents lived). A bronze plaque over the bathroom’s doorway reads “Caldecott Room.”

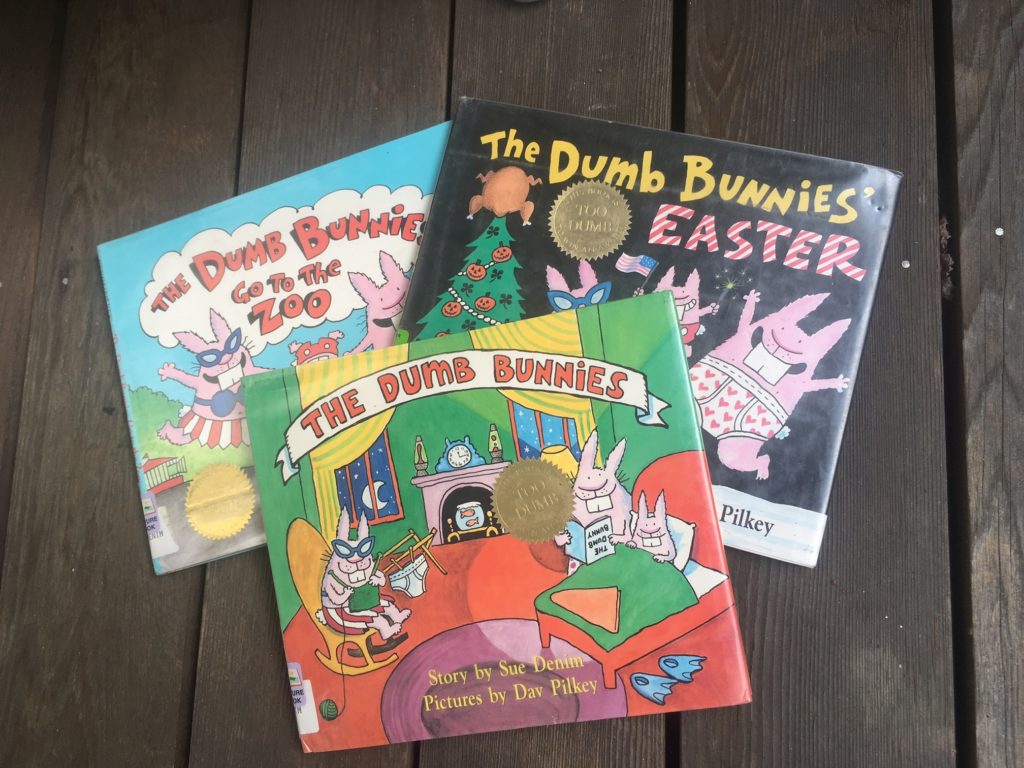

The four-book series is centered around a family of, yep, dumb bunnies who cheerfully go through life underestimating danger, misinterpreting signage and wearing their underwear over their pants. With their punny wordplay, the books remind me a lot of the Amelia Bedelia books (except using references that kids today can actually understand) as well as James Marshall’s marvelous The Stupids.

The four-book series is centered around a family of, yep, dumb bunnies who cheerfully go through life underestimating danger, misinterpreting signage and wearing their underwear over their pants. With their punny wordplay, the books remind me a lot of the Amelia Bedelia books (except using references that kids today can actually understand) as well as James Marshall’s marvelous The Stupids.